There has always been the question of the purpose of the unique skulls of Triceratops. It has been speculated that the horns and frills were used for display, for combat between members of the same species, and/or as tools for self defense. Farke et al. (2009) suggest that fighting between members of the same species may have been at least one use for the horns and frill of Triceratops.

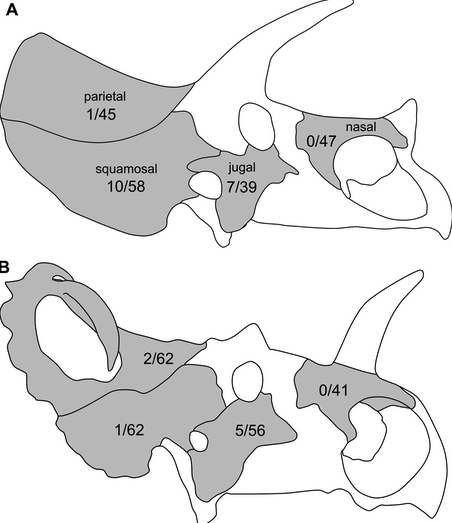

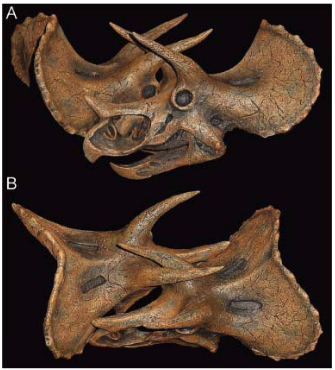

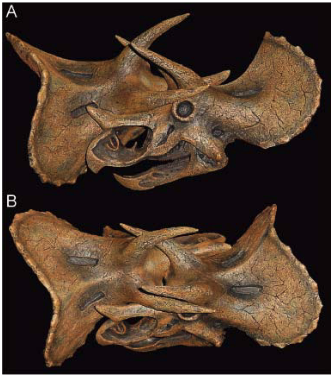

They came to this conclusion after examining the difference between the cranial damage of Triceratops and another type of ceratopsid called Centrosaurus. The idea being that among species with horns that are alive today, the ways in which they engage in combat with other individuals within the same species is associated with difference in horn morphology and location (Farke et al. 2009). For example, it has been suggested that bovid species with twisted horns tend to use a wrestling style of combat while short smooth horns are more typically used for stabbing (Caro et al. 2003). Therefore, different patterns of horn morphology and location should also lead to differences in the patterns of injury (Farke et al. 2009) As such, the differences in the horns between Triceratops and Centrosaurus should indicate different fighting styles which would lead to different patterns of injury in their opponents (Farke et al. 2009). (Please see Exhibits 1 and 2, in order to appreciate the differences between these two types of ceratopsid skulls).

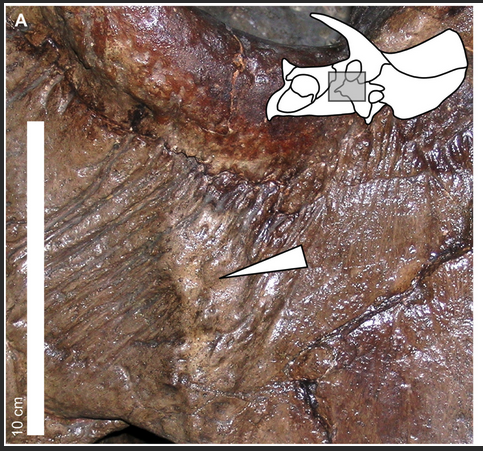

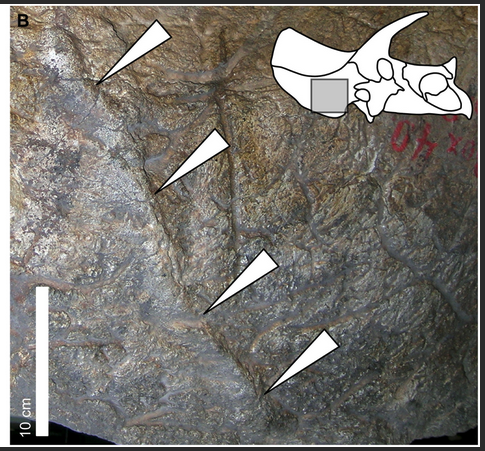

With this hypothesis in mind, the authors examined Triceratops and Centrosaurus skulls for injury. They found that Triceratops skulls had a higher prevalence of injuries on one of the bones of the skull called the squamosal bone as compared to Centrosaurus (Farke et al. 2009). This suggests that Triceratops and Centrosaurus had different fighting styles (Farke et al. 2009).

The authors noted that other possibilities existed that could explain the difference in pattern of injuries. One alternate hypothesis was that there was a disease that caused this apparent injuries to the bone-such as a fungus (Farke et al. 2009). However, the authors rejected this as a possibility because they thought if something like a fungus was reponsible for the skull damage, that the damage should be spread evenly throughout the skulls (Farke et al. 2009). Similarly, the authors didn't think the skull damage was due to predators because similar predators existed in the same areas that both Centrosaurus and Triceratops existed (Farke et al. 2009). Therefore, if the same predators attacked both Centrosaurs and Triceratops, there should be a similar pattern of injury to both of their skull types (Farke et al. 2009).

The authors also noted that the Centrosaurus skulls appeared to have less injuries on them as compared to Triceratops in general (Farke et al. 2009). They suggested that this could mean that Centrosaurus used its horns and frill as display, rather than for fighting, or may have engaged in a different form of combat such as hitting each other's bodies -since there is evidence of rib fractures in Centrosaurus skeletons (Farke et al. 2009).

Another paper by Farke (2004) provides some possibilities in the ways that Triceratops could have engaged in combat with each other, if they indeed did fight each other. They did this by using scaled down versions of a Triceratops skull to see how how the horns could interlock. Farke (2004) suggests that in order for the possibilities of horn locking to have been used in life, the horns could not interlock in a way that the horns hit the nose or the supratemporal fenestrae. This is because this pattern of horn interlocking was likely too dangerous to perform in life as the horns would be hitting weak areas of the skull and increase the risk of serious injuries (Farke 2004). Secondly, the skulls could not be roated more than 90 degrees down from the horizontal because it is unlikely that a Triceratops neck could flex more than that in life (Farke 2004).

With these restrictions in mind, Farke (2004) found that three possible positions of horn interlocking. In the first position, the only contact between the oppenents would be between one of the brow horns of each combatant.

The second position allows for contact between both brow horns of both opponents with the snouts of both animals facing toward the ground (Farke 2004).

In the third position, the brow horns of both combatants are still in contact with each other, and the heads of the combatants are held almost horizontal to the ground (Farke 2004).

Farke (2004), however, does note some caveats to the research conducted. One being that the way that the Triceratops scale models that were used were of the same skull and so had exactly the same skull and horns. In actuality, it is unlikely that two Triceratops would have had exactly the same head morphology which means that there may have been some variations to the three main horn locking positions that they described (Farke 2004). Furthermore, only the bone core of the horns has been fossilized and not the keratin sheath that surrounded it (Farke 2004). Therefore, the horns may have been much larger/longer than what the horn bones suggest (Farke 2004). However, as long as the overall shape of the horn is not changed, Farke (2004) states that the keratin sheath is unlikely to prevent any of the horn locking positions, but instead change the pont of contact between the horns. In addition, the keratin sheath may have also grown in patterns, such as spirals, that are not obvious by looking at the fossils (Farke 2004). However, the author notes that this is a remote possibility since in living species with curved horns, the bone of the horn usually has some curve to it as well (Farke 2004).

First published on: Oct. 26, 2023.